Becoming A SoundCloud Superstar With Fake Fans

FFake views, fake plays, fake fans, fake followers and fake friends – the mainstream music industry has long been about “buzz” over achievement, fame over success, the mere appearance of being everyone’s favorite artist over being the favorite artist of anyone.

Dotted Music thanks Terry Matthew from 5 Magazine for kindly allowing us to repost this article disrobing musicians who buy fake followers on social networks.

Social media has taken the chase for the fumes of fame to a whole new level of bullshit. After washing through the commercial EDM scene (artists buying Facebook fans was exposed by several outfits last summer), faking your popularity for (presumed) profit is now firmly ensconsced in the underground House Music scene.

This is the story of what one of dance music’s fake hit tracks looks like, how much it costs, and why an artist in the tiny community of underground House Music would be willing to juice their numbers in the first place (spoiler: it’s money).

‘Boringly Ordinary’

I’d caught him red-handed committing the worst sin one can be guilty of in the underground: Louie was faking it.

In early January, I received an email from the head of a digital label. In adorably broken English, “Louie” (or so we’ll call him, for reasons that will become apparent) asked me how he could submit promos for review by 5 Magazine.

I directed him to our music submission guidelines. We get somewhere between five and six billion promos a month. Nothing about this encounter was extraordinary.

A few hours later, I received his first promo. We didn’t review it. It was, not to put too fine a point on it, disposable: a bland, mediocre Deep House track. These things are a dime a dozen these days – again, everything about this encounter was boringly ordinary.

But I noticed something strange when I Googled up the track name. And I bet you’ve noticed this too. Hitting the label’s SoundCloud page, I found that this barely average track – remarkable only in being utterly unremarkable – had somehow gotten more than 37,000 plays on SoundCloud in less than a week. Ignoring the poor quality of the track, this is a staggering number for someone of little reputation. Most of his other tracks had significantly fewer than 1,000 plays.

Note the number of playbacks

Even stranger, there were only 117 comments – a very low number for a track with so many plays.

Stranger still, most of the comments – insipid and stupid even by social media standards – came from people who do not appear to exist.

You’ve seen this before: a track with acclaim far beyond any apparent worth. You’ve followed a link to a stream and thought, “How is this even possible? Am I missing something? Did I jump the gun? How can so many people like something so ordinary?”

Louie, I believed, was purchasing plays, to gin up some coverage and buy his way into overnight success. He’s not alone. Desperate to make an impression in an environment in which hundreds of digital EPs are released every week, labels are increasingly turning toward any method available to make themselves heard above the racket – even the skeezy, slimey, spammy world of buying plays and comments.

I’m not a naif about such things – I’ve watched several artists (and one artist’s significant other) benefit from massive but temporary spikes in their Twitter and Facebook followers within a very compressed time period. “Buying” the appearance of popularity has become something of a low-key epidemic in dance music, like the mysterious appearance and equally sudden disappearance of Uggs and the word “Hella” from the American vocabulary.

But (and here’s where I am naive), I didn’t think this would extend beyond the reaches of EDM madness into the underground. Nor did I have any idea what a “fake” hit song would look like. Now I do.

This Is What A Fake Dance Hit Looks Like

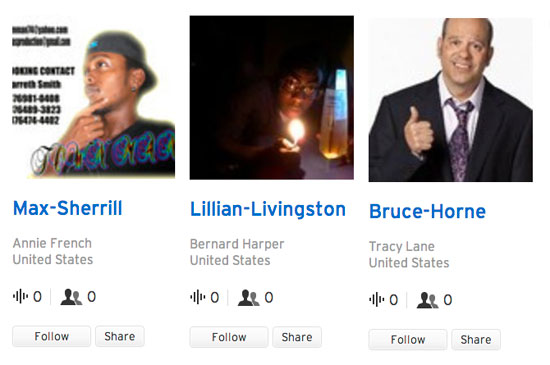

Looking through the tabs of the 30k+ play track, the first thing I noticed was the total anonymity of the people who had favorited it. They have made-up names and stolen pictures, but they rarely match up. These are what SoundCloud bots look like:

Don’t they look suspicious?

The usernames and “real names” don’t make sense, but on the surface they seem so ordinary that you wouldn’t notice anything amiss if you were casually skimming down a list of them. “Annie French” has a username of “Max-Sherrill”. “Bruce-Horne” is “Tracy Lane”. A pyromaniac named “Lillian” is better known as “Bernard Harper” to her friends. There are literally thousands of these. And they all like exactly the same tracks (none of the “likes” in the picture are for the track Louie sent me, but I don’t feel much need to go out of my way to protect them than with more than a very slight blur):

Bots liking the same tracks

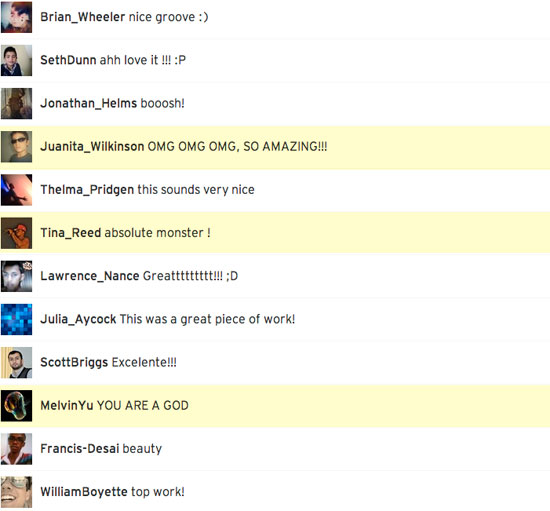

Most of the comments are hilariously banal, but a few do stand out. You have to wonder what Louie thinks, knowing that comments like “YOU ARE A GOD” come from imaginary fans he’s paid for:

YOU ARE GOD

Most of them are like this. (Louie deleted this track after I contacted him about this story, so the comments are all gone; all of these were preserved via screenshots. He also renamed his account.)

Fake Plays, Real Dollars

It’s pretty obvious what Louie was doing: he’d bought fake plays and fake followers. But why would someone do this? After leafing through hundreds of followers and compiling these screenshots, I contacted Louie by email with my evidence.

His first reply consisted of a sheaf of screenshots of his own – his tracks prominently displayed on the front page of Beatport, Traxsource and other sites, along with charts and reviews. It seemed irrelevant to me at the time – but pay attention. Louie’s scrapbook of press clippings is more relevant than you know.

After reiterating my questions, I was surprised when Louie brazenly admitted that everything implied above is, in fact, true. He is paying for plays. His fans are imaginary. Sadly, he is not a god.

You have noticed that I’m not revealing Louie’s real name. I’m fairly certain you’ve never heard of him. I’m hopeful, based upon listening to his music, that you never will. In exchange for omitting all reference to his name and label from this story, he agreed to talk in detail about his strategy of gaming SoundCloud, and then manipulating others – digital stores, DJs, even simple fans – with his fake popularity.

Don’t misunderstand me: the temptation to “name and shame” was strong. An early draft of this story (seen by my partner and a few other people) excoriated the label and ripped its fame-hungry owner “Louie” to pieces. I’d caught him red-handed committing the worst sin one can be guilty of in the underground: Louie was faking it.

But when every early reader’s response was, “Wait, who is this guy again?” – well, that tells you something. I don’t know if the story’s “bigger” than a single SoundCloud Superstar or a Beatport One Week Wonder named Louie. But the story is at least different, and with Louie’s cooperation, I was able to affix hard numbers to what this kind of ephemeral (but, he would argue, very effective) fake popularity will cost.

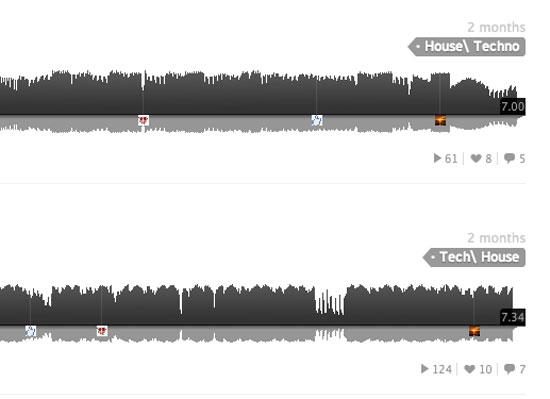

This is “Louie’s” actual level of popularity – tracks that were put up months before he began gaming the system.

This Is What A Fake Dance Hit Costs

Louie told me that he artificially generated “20,000 plays” (I believe it was more) by paying for a service which he identifies as Cloud-Dominator. This gives him his alloted number of fake plays and “automatic follow/unfollow” from the bots, thereby inflating his number of followers.

Louie paid $45 for those 20,000 plays; for the comments (purchased separately to make the entire thing look legit to the un-jaundiced eye), Louie paid €40, which is approximately $53.

This puts the price of SoundCloud Deep House dominance at a scant $100 per track.

But why? I mean, I’m sure that’s impressive to his mom, but who really cares about Louie and 30,000 fake plays of a track that even real people that listen to it, like me, will immediately forget about? Kristina Weise from SoundCloud told me by email that the company believes that “Illegitimately boosting one’s follower numbers offers no long-term benefits.”

But to hear Louie tell it: it does.

If you are interested in the story, read the rest of it at 5 Magazine’s website.

Comments

Comments are closed.