Music Production Evolution: The Rise Of Digital Vs. The Vinyl Revival

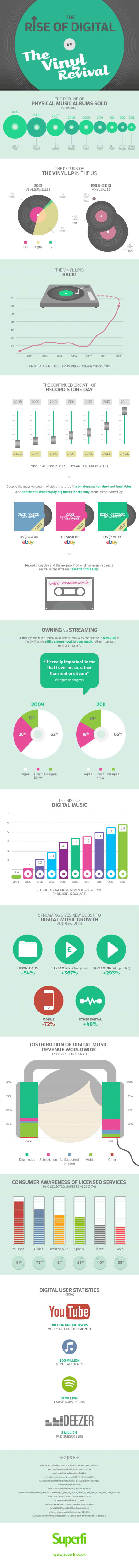

TThe unexpected sales success of music formatting last year has been labelled ‘The Vinyl Revival’.

We’ll delve into how and why the cult following for vinyl has resurfaced in this booming digital age. Alongside this, we’ll question the popularity of digital and what this could mean for the music industry.

Enjoy this thought piece as we challenge the evolution of our music culture.

Beginning with the figures of the deeply deliberated revival of vinyl, things became press worthy when it was discovered that 6.1 million LPs were sold in America in 2013. This trend also crossed the pond to us Brits who saw the best sales in vinyl for over a decade – 287,000 vinyl LPs purchased, double the number in 2012! Our Aussie friends joined in too, as they saw a 75% spike in vinyl sales during this same period.

To put this into perspective, vinyl counts for less than 2% of US music record sales and in the UK roughly only one vinyl is sold for every 250 records purchased. However, the revival still holds momentum – especially for UK independent record stores, who saw a 44% increase in sales last year. They can thank the vinyl, with an LP sold once in every 7 times an album was sold.

But the plot thickens.

It’s easy to presume that people who purchase vinyl are seeking a flash back to the past. Wrong. Last year the bestselling vinyl (in both the US and the UK) was Daft Punk’s album Random Access Memories, seconded by Vampire Weekend’s Modern Vampire’s City (both released May 2013). Vinyl is becoming a popular platform for artists to release their latest albums on.

Furthermore, more confidence in vinyl can be found from the national music event called Record Store Day. Held every April, collectors can queue to snap up exclusive vinyl editions of big brand artists. Last April (2014), 133% more vinyl records were sold the week of this national event compared to the previous week. The popularity of this event suggests that some artists and collectors are still attracted to this vintage music format, even in an environment full of digitally perfected sound.

However, if we open up the picture, things get a little less impressive for vinyl. Firstly overall physical album sales has been on a steady decline for the last decade; just compare the 598.9 million albums sold in 2005 to the 206.4 million albums sold in 2013.

With this in mind, it probably comes as no surprise that iTunes entered the market in 2003! At the beginning, in 2004, the global digital music revenue was 0.4 billion U.S. dollars which has since boomed to a whopping 5.9 billion in 2013.

Ultimately, given the choice, people are choosing digital.

As a consumer, to purchase a physical album, such as a CD, costs around £10. This is considerably more than downloading. For big labels to print physical albums usually costs between $0.50 – $0.65 per CD and $1.50+ per vinyl record. These are big upfront costs, which together with the production and promotion of the music creates a huge risk before the album can be commericalised. Yet risk is the nature of the music industry; according to the Recording Industry Association of America approximately 90% of all records released by major labels fail to make a profit.

Hypothetically downloading music should reduce the upfront cost of releasing an album; as manufactures don’t need to pay for the components of a physical album. Yet whilst in theory digital music should offer artists greater profit, this is not the case. The standardised format of digital music has made sharing music easier than ever (interestingly, a rival format to MP3 which restricted the ability to share music was rejected by consumers). Therefore alongside the growth of the MP3 format (which was introduced to the market through CDs), there has been a growing expectation that users are entitled to listen to and share music for free. This is threatening the profitability and sustainability of the music industry.

Furthermore, the desire to own songs is fading.

An even easier and quicker way to access music compared to purchasing CDs and downloading songs is streaming; whereby users play music straight from a library of songs on the internet. The first major example of this was people using YouTube to listening to their favourite songs for free.

A response to this has been the development of streaming subscription services; such as Spotify, Napster and Beats.. These platforms try to encourage consumers to pay for listening to their database of music, usually through a monthly subscription fee. Whilst some money from subscription fees does go back to the artist, the majority goes to the music labels who usually own the rights to the songs. The streaming subscription services have to pay huge upfront royalty fees to the labels in order to legally have the music on their database.

Due to these costs, the music label fees per stream are low, consequently artists make little money from streaming services and the popularity of their song has little effect of their pay check.

Furthermore, streaming businesses are reinforcing consumers to not purchase songs via downloads or CDs; making the music industry even harder for artists to live off. It was calculated in an infographic by David McCandless that an artist on Spotify needed over four million streams per month to earn $1,160, which is the equivalent of a full time job at minimum wage. Some artists, including members of Biffy Clyro, Radiohead and The Black Keys have all publically spoken or acted against these streaming services. Yet the popularity of these subscription models continues to grow, with over 350% more people signing up in 2013 compared to 2008.

Another interesting point to note here is that these services are not making a profit. There are many critics who believe that they will never make a profit with their current business model.

In comparison to streaming, the revival of vinyl popularity is a great testimony to buying and owning music. However the accessibility and ease of streaming music means it is unlikely for vinyl or any other physical form of album to become the mainstream format again; so much so that it has been predicted that by 2020 purchasing individual songs and albums will become a thing of the past.

This leads us to wonder what the future of the music industry will become, as the chances of creating a profitable album becomes even harder.

Source: superfi.co.uk

Comments